Table of Contents

ToggleDid the Real Inventor of Monopoly Lose Her Game? The Elizabeth Magie Phillips Story

What do you get when you cross a landlord, two patents, an economics professor, the supreme court, and a dirty little secret?

Can you remember inhaling that deep breath as you pick up the dice. They tumble in your hands as you look to the board, eyeing the perfect spot of safety. Your breath exhales as you spill the dice onto the board. Please, not Boardwalk. Please, not Park Place. Four or higher, you whisper in your mind. It’s a three. You were almost to Go. Almost. You sigh as you look at your last $100 and sigh as you hand it over to Miss Bossypants (your big sister). There will be mean looks at dinner. Monopoly got you again.

The Origin Story

You may have heard the origin story of Monopoly. In the middle of the Depression, Charles Darrow, an unemployed, down-on-his-luck heater man, came up with an ingenious idea. He took it to Parker Brothers and went from rags to riches—earning more than 1 million dollars! The truth about the real origin story would remain a secret until 1973.

Lizzie Magie

Enter Lizzie Magie. She was born in Illinois in the mid-1800s. Her father was an influential newspaperman, and through him, she was introduced to the idea of a Single Tax. Like others before her, she saw capitalism negatively. Because home ownership was limited to only the wealthiest in the country, she observed that paying rent to these wealthy men was only making them wealthier and “the little guy” poorer. She found the practice to be a monopoly on the market.

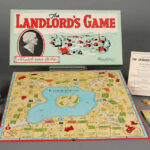

Landlord's Game

Lizzie Magie decided to make a game that would demonstrate these principles. She set up the board with properties like “The Poorhouse,” “Beggarman’s Court,” and “Gee Whiz Railroad.” On January 5, 1904, Lizzie got a patent to protect her rights to the game. She went to Parker Brothers, hoping they would produce the game, but they turned her down. So, she created the Economic Game Company and produced the game herself. Having a patent and making a game was unusual for a female in the early 1900s.

Everyone's Playin'

The Landlord’s Game caught on, especially with the college crowds. The object of the game was to gain the most wealth. Multiple colleges and groups of students passed the game around, making their own boards and adjusting the rules. Many of those versions have been destroyed. It is unclear whether Lizzie knew that multiple versions were being made, but she did know it was popular. She sought another patent for the game in 1924.

Do Not Pass Go

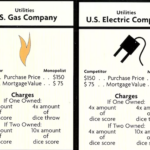

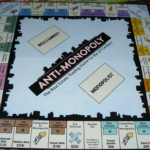

Charles Darrow’s origin story would have gone unchallenged, but in 1973, Parker Brothers sent a cease-and-desist letter to Professor Ralph Anspach for his creation of a game called Anti-Monopoly. Ralph’s game differed from Monopoly, and he pushed back. He sued Parker Brothers, claiming they had no rights to their game. He wasn’t sure how he would win the lawsuit until he started doing an investigation.

Ralph traced the history of the Landlord’s Game to Monopoly to prove Charles Darrow stole the idea from someone else. Ralph discovered that professor Scott Nearing, from the Wharton School of Finance, shared the Landlord’s Game with students, including a group of Quakers in Atlantic City. Jesse and Eugene Raiford were among the group that became aware of the game. The Raiford brothers modified the game by using household objects as pieces and renaming the properties for areas around Atlantic City.

The property names were not coincidental. The first set of properties on the board, Mediterranean and Baltic, were named after the segregated part of the city. These properties are the cheapest on the board. Other names reflected Jewish and middle-class communities. As the player moved around the board, the properties became more expensive. Boardwalk, as in the Atlantic City Boardwalk, was the most expensive property on their version of the board.

Just Visiting

Ralph is about to uncover the connection between Magie and Darrow when he sits down with Charles Todd. Todd told Ralph that he was part of the Atlantic City Quakers. Through this connection, he was introduced to the new version (called monopoly) with properties from Atlantic City. Todd and his wife had the Darrows over to play the game one night. The next day, Darrow called Todd and asked him for the written rules. Todd had his secretary write up the rules and send them to Darrow. Darrow did have a connection to Magie, after all!

Todd didn’t hear from Darrow again. One day, he noticed a sign at the bank inviting people to see Charles Darrow’s new game, Monopoly. He was shocked. Ralph was, too. He had just finally found the connection between Darrow and Magie.

Bankrupt

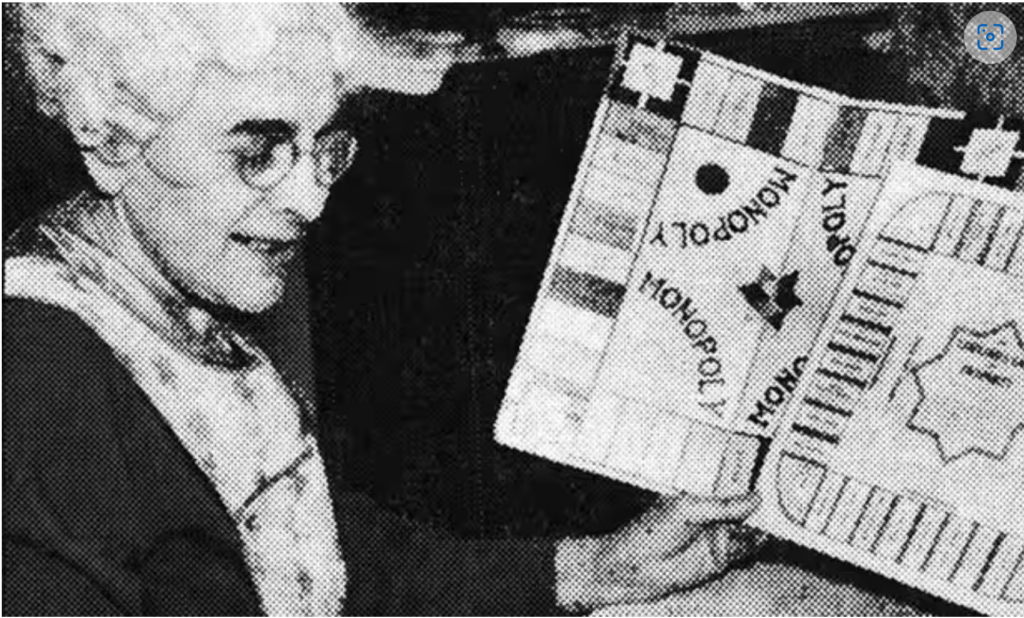

As Ralph continued to investigate, he discovered that Parker Brothers knew about the game’s previous versions. Magie went to the press in 1936 to show she had created the game first. In a deal with Parker Brothers, she sold her patent for $500 without royalties. While Darrow earned over $1 million, Magie had lost—to a monopoly.

Anti-Monopoly

Ralph Anspach went on to lose his case against Parker Brothers. The day before trial, Parker Brothers offered him $2 million with the agreement that he would never discuss Magie or the history of Monopoly. He declined, and the next day, the judge ruled against him, ordered him to turn over all his Anti-Monopoly games, and prohibited him from talking about the history of Monopoly.

But we all know, in Monopoly anyway, it’s not over until it’s over. Ralph mortgaged his properties (you can’t make this stuff up) and brought his case to the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court ruled in his favor. Sometimes, the little guy does win.